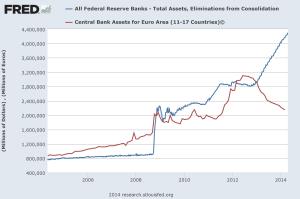

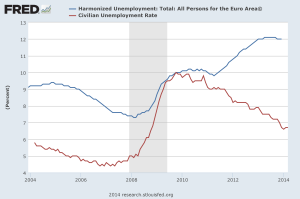

This is a version of my column in the Irish Examiner of 26 April 2014. Macroeconomics is hard. Its hard because there are actually few coherent theories, such internally coherent theories as we have oftent tend to be at odds with reality, data are of fairly low frequency (monthly usually) and we cant run experiments usually. Those of us who are not practicing macroeconomists thus tend to fall back on fairly simple rules of thumb when assessing policies and outcomes, often by reference to the past. Thus in Europe the ECB has in fact run an experiment against the Federal reserve board. While the Fed has taken the lessons of the 1930s on board and expanded its balance sheet, the ECB has taken the lessons of the 1920 on board and done so reluctantly and is now unwinding them. While the USA engages in quantitative easing, the ECB has engaged in quantitative squeezing. And the results are in; look at the comparative unemployment, performance of the two regions which is really the key metric any sentient or ethical policymakers should concern themselves with. Yes, the USA has an advantage in that they cleaned the banks earlier than did the Eurozone, and thus the monetary transmission system, such as it is in the modern world, was able to work. But that aside it is striking how in recent years the two banks have diverged. It is reasonable to infer that the experiments have had different outcomes.

Correlation is not causation. But the policy levers that can be pulled on economies are broadly two – fiscal and monetary. A glance at the directions of the levers and the outcomes suggests that there must be either some connection or there are other countervailing levers being pulled. Both the US and Euroxone fiscal stances have been of a similar trajectory over the last while, so we can rule that out. Yes, there are issues in the Eurozone around such things as labur market policies and the rate of technological innovation which are more of a concern than in the USA but can these really explain the divergence?

A huge part of the ECB reluctance to engage in massive quantitative easing, even were it to be effective, lies in culture. The ECB has a mandate on price stability, it is true, but mandates are interpreted in the here and now. Even were Trichet and Draghi willing to go QE the culture of the ECB is not one that would allow this. A large part of this is down to the fact that the ECB is best understood as the heir and successor to the Bundesbank, which famously and for German historical and cultural reasons was hypersensitive to any inflation. This in turn plays into and is a product of the macroeconomic idea that QE=Inflation (eventually), as inflation is “always and everywhere a monetary phenomena” as Friedman noted. Except of course, its not. Without getting into the technicalities for that to be true would require a number of other things to be the case, notably that money would circulate at the same speed all the time (the velocity of money is constant) and that the quantity of goods grew slower than the growth rate of the money supply. These factors are not in play in the Eurozone now and perhaps never were.

The ideas behind the money=inflation were not formalized by Friedman, whos work was of course considerably more nuanced than its popularizing money growth = inflation monetarist misery mcnugget would indicate. They were in fact originated by John Stuart Mill and formalized by Irving Fisher.

There is a recent debate in the macroeconomic literature on the issue of the relationship between inflation and interest rates, but this is both very new and very controversial. The implication of this neo-fisherite school, as it is now being called, is that high interest rates cause high inflation and low rates cause deflation. Not being a macro theorist I will sit the debate out, but there is clearly a growing concern within Europe of disinflation or actual deflation. Most conventional models (which may be wrong of course) would suggest that while putting money into the economy may result in inflation in the long term taking money out will not help. And the ECB has been taking money out. This is not a good idea. The argument appears to be as noted by the chief economist of Allianz recently, that the large current account surpluses of the Eurozone runs the risk of inflating a bubble in credit and asset markets. However, the Eurozone current account surplus is a product of a massive german surplus, slightly smaller dutch and Italian (import collapse driven) ones and the rest are small beer. Again the cultural issues are important. A tight money bundesbank led , in the long run, to the german export miracle stuttering through a combination of high domestic costs and faltering exports. We are now seeing the return of tight money ideals, but this time in an environment where export driven growth is the aim.

The ECB can be brave. That’s not something Central Banks like to be. They can insist on proper stress tests, and thus revealing just how badly damaged the European banks are. They can then pump in as much money as is needed to refloat them, which is consistent with price stability in the long run and it can relax. Or, it can continue to obsess with non-existent inflation fears and tighten the screws.

Reblogged this on Machholz's Blog.

Reblogged this on Awaken Longford.